A simple, beautiful thing happened on the farm this past week.

Members brought corn seeds that they had saved in their homes over the winter back to the farm to be planted.

In doing so, they performed perhaps the most vital agricultural act, saving seed. This act, in ways that are as practical as they are divine, connected us to each other; connected our kitchens and homes to the Earth; and connected us to time and to ancient ancestors and distant descendants.

“Whoa, dude, get a grip… We just saved some of those corn cobs on our dresser.”

Precisely!

So the story goes...

There once was a man in Montana looking for a flour corn suited to the short, tumultuous summers. He reached out to friends, who reached out to their friends, and he gathered as many heirloom corn varieties as he could. He was given seeds from the Intermountain West and the Dakotas; seeds from the Desert South and the Deep South; seeds from the East, and the West; seeds from Native Americans, from European homesteaders, and from African American farmers. Then, one Spring he planted them out in the same field together and let them cross, and that Fall, he harvested. He chose the ears that he liked best — the ones that were beautiful; the ones that produced a lot of seed; the ones that had a hard, protective shell; and the ones that gave sweet flour -- and he saved them. He planted those out the next Spring and so on and so forth.

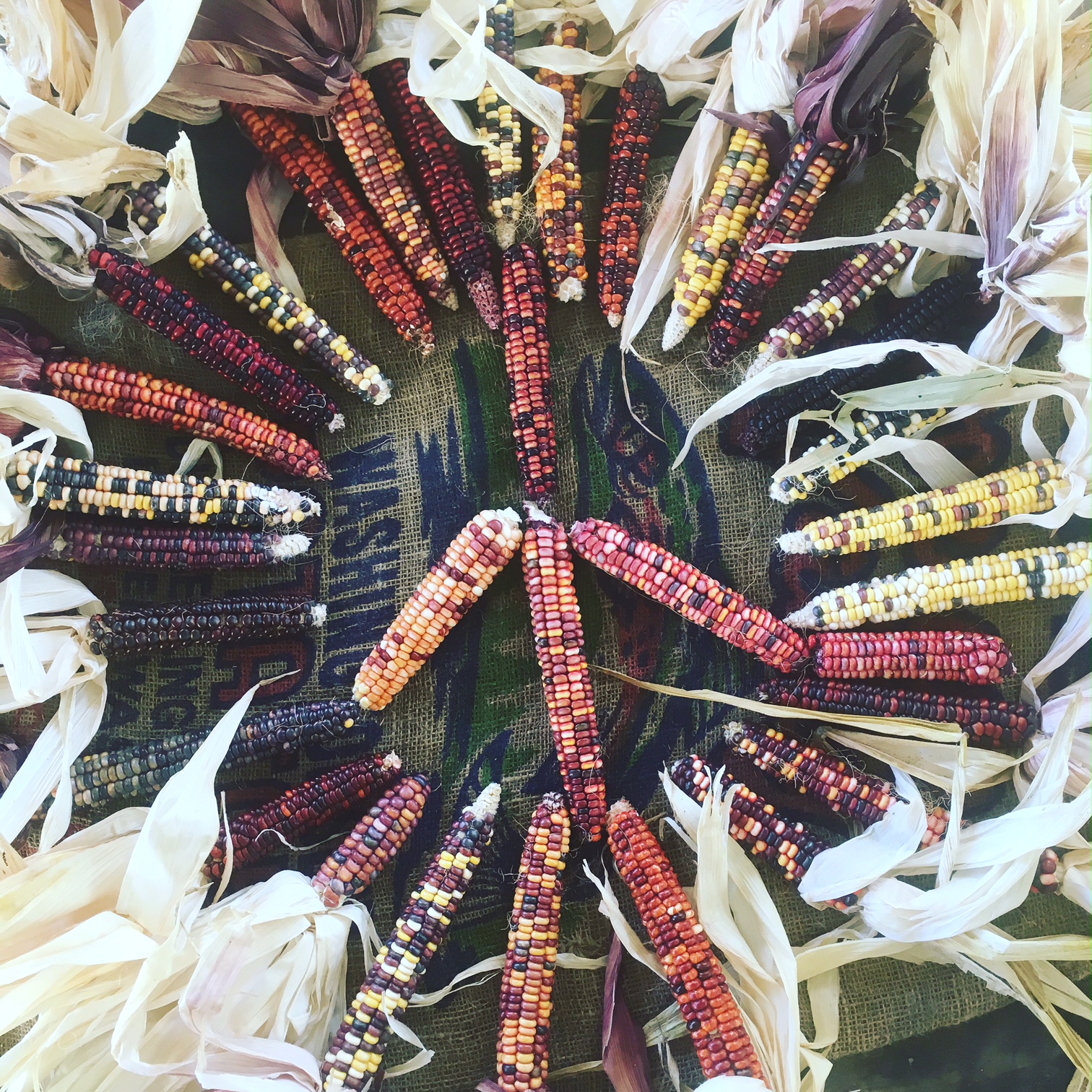

After many years, this corn became known as Painted Mountain: A gorgeous, multi-colored, hearty, early flint heirloom that contains within each kernel, in a very real way, an immense genetic diversity and history; genes baring the mark of numerous peoples and cultures selecting for their needs, their desires, their histories, their stories, and their lands. These genes bare the history of people who lived and died by their corn, who were reared on it and fed their children the same corn their great-great grandmothers saved.

Kayta and I planted some Painted Mountain seeds in our East Field last spring next to the Jack-O-Lanterns. They didn’t all do well. Some didn’t thrive. Some were cut down by wire worms. But some grew strong.

Some of you may remember the hot September day we harvested that patch, eating bagels and cream cheese under the willow, and marveling at the explosions of color behind each husk.

We brought the harvested ears into our greenhouses to dry, and a few weeks later we threshed them and milled the kernels into flour at Tierra Vegetables. Then came the best part… We made pancakes and breads and cakes. And for a brief moment, our bodies and our thoughts were made of Painted Mountain Corn.

But some ears we didn’t thresh or mill. Some were so beautiful that they took our breath away. The wine-dark red ones, the impossibly orange, the muted pastel mosaics of greens, purples, and blues. These, we kept, and took home and to adorn our kitchens, our mantles, and our dusty dresser drawers.

When we chose ones we liked, that simple act of affection and appreciation for beauty, we did it without even knowing it… we performed the most ancient, important agricultural act. We selected for plants that did well that summer, in this soil, in this climate, on this farm.

Over the winter, those seeds we protected in our homes. They listened to the winter rains patter on our roofs and to the laughter, the tears, and songs in the house. And then we brought them back to the farm to plant.

It strikes us that in this simple moment of seed saving, perhaps we became what our name aspires to: We became a community farm.

A bold statement -- but nothing could be truer. In taking a small step toward adapting this powerful, sacred staple food crop to this land, we simultaneously honored all that went into those seeds before they came here... and a settled future. We chose interdependence to this place, to this seed, and to each other.

Thanks for being a part of this farm community!

Well how’s that for a sappy Farmer’s Log? Next week, we’ll have to write about tractor maintenance or something!

See you in the fields,

David and Kayta